Franklin Park Defenders blast city's White Stadium traffic plan

The city’s traffic planning for the redevelopment of the White Stadium has been riddled with contradictions and unsupported assumptions, according to a traffic planner hired by the Emerald Necklace Conservancy.

The city’s traffic planning for the redevelopment of the White Stadium has been riddled with contradictions and unsupported assumptions, according to a traffic planner hired by the Emerald Necklace Conservancy.

Traffic planner Bill Lyons told reporters the city’s plans for bringing spectators to the planned 11,000-seat women’s professional soccer venue via shuttles, ride shares and for accommodating pedestrians walking from the Orange Line are unrealistic.

“The project’s analyses rely on flawed data comparing this project to Fenway Park instead of other facilities of comparable attendance, scale and context,” he said, speaking during a press conference Wednesday.

“It is a concept of a plan that is not going to work for this community,” said Renee Stacey Welch, a plaintiff in the lawsuit backed by the Emerald Necklace Conservancy.

The city’s most recent iteration of a transportation plan — released April 25 — calls for up to 6,600 people to arrive to the station on shuttle buses that will ferry them from MBTA stations and remote parking sites. The city has not yet identified where the remote parking sites would be situated. It also estimates up to 2,200 people arriving from MBTA stops, 1,100 riding bikes or walking and 1,100 using ride shares.

How the ride shares and shuttle buses would make it into and out of the park remains unclear, Lyons said.

“In the April 2025 document, the city did not submit any traffic analyses to help the public understand the impact of the projects on local streets,” Lyons said.

A spokesperson for the city responded to Lyons’ report with a statement.

“Franklin Park has always been home to large events, including some of the City’s most beloved annual concerts and cultural festivals that regularly draw tens of thousands of attendees,” the statement reads. “But until now, there has never been an organized transportation plan to actively coordinate and manage traffic, parking, and enforcement. The renovated White Stadium transportation plan will set a new standard for crowd events in Boston: residents will benefit from new resident parking and visitor passes, visitors will travel on team-provided electric shuttles, and Franklin Park users will have their access to the park protected.”

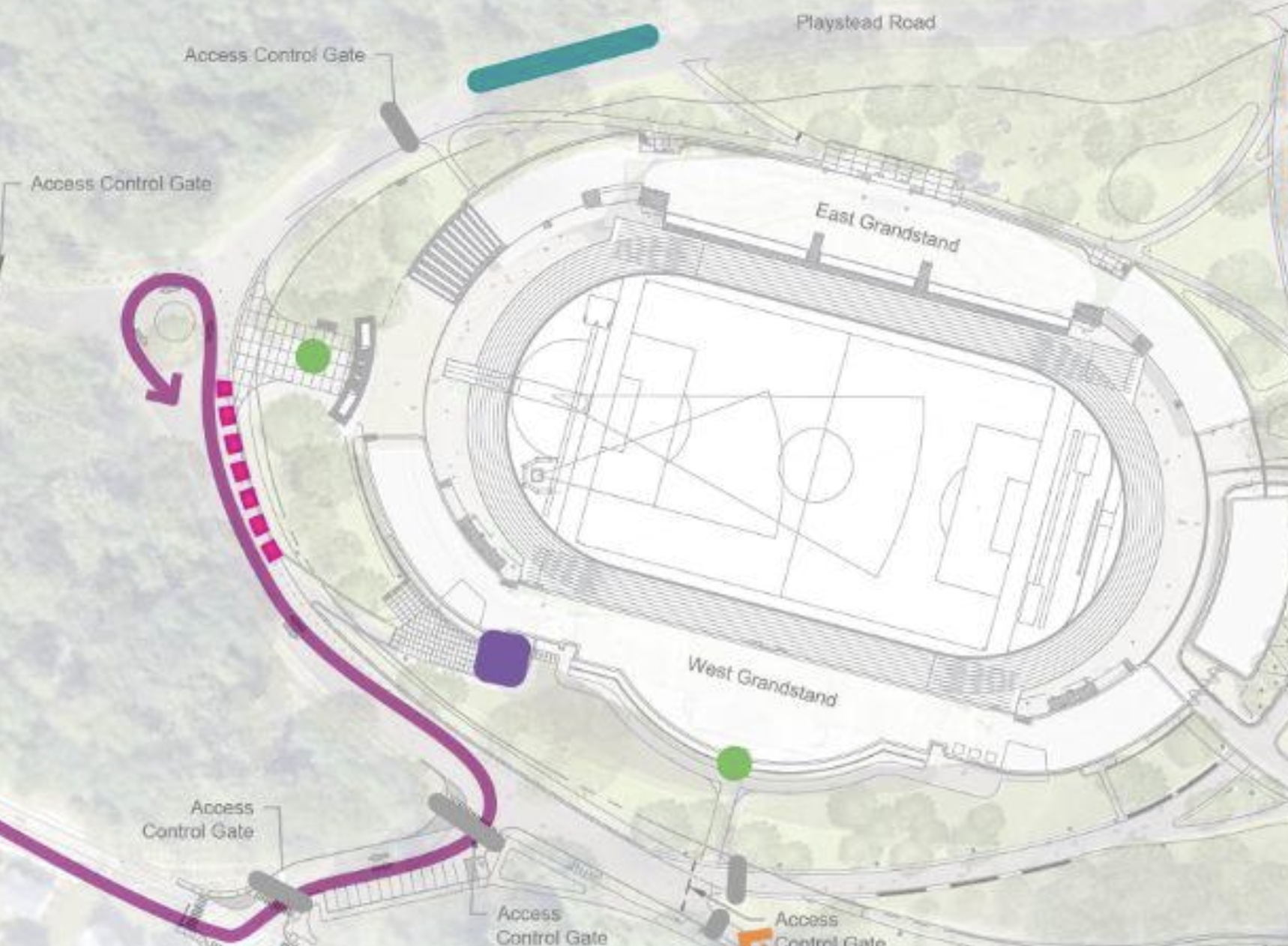

Under the city’s April 25 plan, 40 shuttle buses would arrive at White Stadium via Walnut Avenue and discharge passengers along the western side of the stadium, then turn around at a yet-to-be-constructed traffic circle and exit the park via the stadium’s Walnut Avenue entrance. Lyons said the city has not appeared to conduct a traffic study to determine the effects of the shuttle traffic or rideshare trips to the stadium.

The shuttles entering via Walnut Avenue would bring passengers from remote parking facilities and the Ruggles Orange Line station.

The plan calls for 104 shuttle buses to discharge passengers at an existing parking lot on Circuit Drive: 30 from the JFK/UMass Red Line station, 25 from remote parking would enter via Blue Hill Avenue and 49 would arrive from remote parking via the Arborway and from the Forest Hills Orange Line station.

Lyons told reporters the planned shuttle trips, totaling as many as 144, would require a football field-length of curb space in order for buses to arrive and depart every minute, as called for in the plan. Because it takes a minimum of three minutes for a fully- loaded bus to discharge passengers, multiple buses would have to compete for curb space that does not yet exist.

Creating space for the shuttle buses could spell legal trouble for the city.

A Suffolk Superior Court judge in April ruled against a Franklin Park Defenders lawsuit that sought to block the city’s lease of the stadium to Boston Unity Soccer Partners on the grounds that the arrangement was effectively privatizing park land. In his April 2 ruling, Judge Matthew Nestor ruled that the stadium, which was transferred to the ownership of the Boston Public Schools, is not park land.

But Karen Mauney-Brodek, president of the Emerald Necklace Conservancy, said during the Tuesday press conference that the city’s plans to use land that surrounds the stadium for shuttle buses would constitute a taking of park land. The land surrounding the stadium is not owned by Boston Public Schools. Mauney-Brodek says the surrounding parkland is protected by the state’s Public Lands Act. The city’s plan to bring shuttle buses into parkland for Boston Unity Soccer Partners benefit would violate state law, she said.

“It’s an easement for access for people to use for a leased or for-profit entity inside what is public space that was established to be public space,” she told The Flipside.

In his remarks to reporters, Lyons also questioned the city’s estimates of 1,100 trips to the stadium via ride shares and the city’s plan to site drop offs and pick ups for ride shares at the Seaver Street entrance to the park opposite Humboldt Avenue.

“At this point, it is hard to take any of these trip generation analyses at face value as the city has abandoned any pretense of using a scientific method to project the number of new trips the site will generate for the soccer matches,” he said.

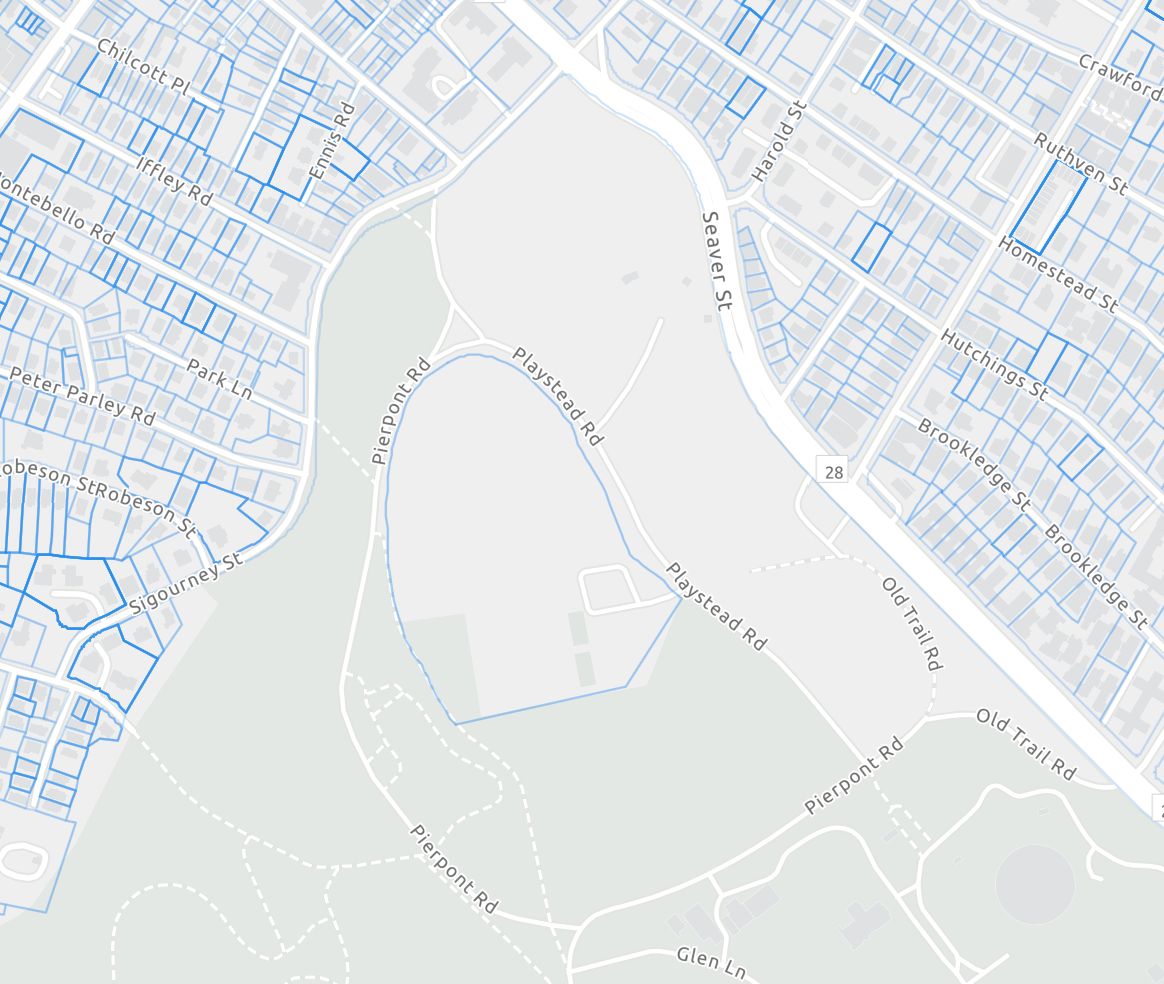

Others at the Tuesday press conference spoke about the city’s planned parking ban, which would allow parking only for those with resident permit parking stickers provided to those who live within a proposed White Stadium parking district, an area within about a mile of the stadium. The proposed district would include Grove Hall, follow Warren Street to Martin Luther King Boulevard, come a block shy of Jackson Square and extend along Chestnut Ave to Green Street in Jamaica Plain.

The parking ban would remain in effect from 3 p.m. until as late as 10 p.m. on game days. Those lacking a parking permit would be ticketed $100 and towed, under the city’s plan. It's not clear how businesses in commercial districts such as Egleston Square and Grove Hall would function with such a parking ban.

“They’re creating something that is going to make life extremely difficult for the people who live here for people who would not even want to live in this community or be part of this community,” said Renee Stacey Welch, a plaintiff in the Franklin Park Defenders lawsuit against the city. “There is no care about our community when you don’t think about what is going to be the bad part of all of this.”