Joseph Clash: A 19th century gangster/entrepreneur

At a time when Black Bostonians were effectively locked out of the city's job market, crime and business ownership were two means for survival. Joseph Clash excelled in both arenas.

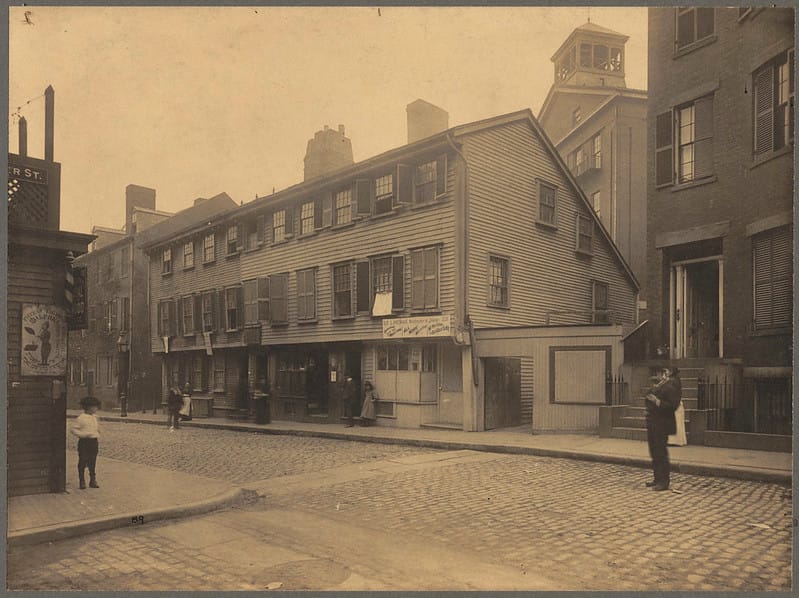

When two white men entered Joseph Clash’s North End barbershop on Feb. 2, 1863, he probably thought little of their arrival. A well-known figure in the neighborhood where most Blacks lived in Boston at the time, Clash had made a career of catering to the needs of whites in his various enterprises, which included a restaurant, a dance hall, a catering business and, for a short time, a brothel.

But after receiving a shave from Clash, customer John Rogers attempted to purloin a book from the premises. Confronted by Clash, Rogers responded by striking him. What followed next was quoted in the Feb. 3, 1863 edition of the Boston Herald:

“Joe is not the man to be assaulted with impunity. No sooner was he struck than he drew his revolver, and told his assailant before he struck again to gaze upon that weapon. ‘Damn your old gun, it ain’t loaded!’ said Rogers.”

Those were Rogers’ last recorded words. After Clash fired a warning shot into his shop floor and Rogers continued to advance, Clash shot him in the torso. Rogers died the next day in Massachusetts General Hospital.

What happened next demonstrated the strength of Clash’s connections, built over decades of catering to the various needs of Boston residents, including politicians and police. Clash, defended by Robert Morris, a man historians have referred to as “the first really successful colored attorney in the United States,” argued the shooting was in self-defense. “A number of Police officers testified to his good character,” noted the Boston Traveler in an article published on March 13 of that year.

A jury that was almost certainly majority white — given that Blacks then made up less than 2% of Boston’s population — returned a not-guilty verdict and Clash returned to cutting hair.

Born in Salem in 1808 to Joseph and Patience Clark, Clash had changed his surname by 1827 when he was sentenced to a four-year term in a state penitentiary for larceny. By 1840, Clash owned his first barbershop — an impressive feat for a Black man in Boston at the time.

In her book, “No right to an honest living — The struggles of Boston’s Black Workers in the Civil War Era, historian Jacqueline Jones paints a picture of a Black workforce largely excluded from all but the most menial jobs in Boston’s labor market. Within that context, Clash’s success in legitimate and criminal enterprises was exceptional.

“Clash was a fascinating figure,” she said in a recent interview. “We was an entrepreneur, a musician, a card sharp, a barber. You could imagine him making a mark in the legitimate world if he had the opportunity.”

While Blacks in Boston had, by 1863, secured the right to vote, to right to serve on juries and attend integrated schools, the city’s labor market remained segregated, with most Black men serving as day laborers.

“The average Black man didn’t know what work they would do until they gathered on a street corner,” said historian and former state Rep. Byron Rushing. “Business owners would pick them to do odd jobs.”

Most Black women in the labor market worked as servants to white families.

Professional Black men were few and far between. Clash’s attorney, Robert Morris, worked as a servant for white abolitionist attorney Ellis Gray Loring who tutored him in law, helping him pass the bar in 1847. Abolitionist Lewis Hayden, earned money speaking about his escape from slavery in Virginia and opened a clothing store that was the second largest Black business in Boston, before he became a legislator in 1873. Abolitionist David Walker, whose 1829 “Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World” pamphlet urging Blacks to actively oppose slavery was banned in Southern states, opened a clothing store, although he and two other merchants were tried in 1828 for selling stolen goods.

All successful Blacks relied heavily on white patronage to succeed. Morris, a Catholic, did legal work for the Catholic church and for many of the recent Irish immigrants arriving in Boston. Barbers such as Clash relied on white clientele.

“Black people didn’t cut Black people’s hair for money,” Rushing notes.

Even in his criminal enterprises, Clash’s clientele was largely white. In fact, Clash’s establishments — restaurants, dance halls and prostitution rings — were among the few spaces where Blacks and whites mixed in Boston.

In another Boston Herald report, published Feb. 3 of 1863, a reporter paints a vivid picture of Clash’s milieu:

“The name of Joe Clash is a household word, at the North End, the owner of it having been identified with the history of that part of city for many years. It is unnecessary for the information of any of our urban readers, to state that he is a colored man, now becoming somewhat venerable, or that he kept, for a long time, the most celebrated of the dance halls on North street and its vicinity, where very recherche concerts were given, and where fast young men, white and black, met the sable belles of that locality in free and easy intercourse, untrammeled by the ordinary restrictions of the ball-room.”

By the time of the article, Clash had limited his entrepreneurial pursuits to hair cutting. But after John Rogers took his last steps in Clash’s shop, Clash found himself again in court.

While in years past, Clash had almost certainly paid off police officers to stay out of jail, it’s unclear whether he was actively involved in any criminal pursuits by the time of the 1863 shooting.

After a career of catering to the wants of Bostonians of all stripes, Clash may have built up a store of goodwill, Jones says.

“He had so insinuated himself into the life of the city that juries of the time wouldn’t convict him,” she said.

Nine years after the shooting, Clash, perhaps hobbled by rheumatism and in the midst of what in the 19th century counted as old age, one day closed up his shop at noon, left a note for his wife, descended into his basement and shot himself. He left behind his fourth wife, three ex-wives and seven children. He was buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery in Everett.