Wu says Boston police won't work with ICE, but activists fear they already may be

While local officials say Boston Police will not assist federal agents in the Trump administration’s deportation efforts, Boston police have for more than 20 years shared information with federal authorities that activists say has aided ICE in targeting and deporting immigrants.

Surrounded by local elected officials, labor leaders and immigration activists, Mayor Michell Wu delivered a firm answer to U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi’s demand that the city eliminate laws barring local police from assisting federal immigration authorities in their deportation of immigrants.

“The U.S. attorney general asked for a response by today, so here it is,” Wu said Tuesday, speaking before a crowd of several hundred gathered at Boston City Hall Plaza. “Stop attacking our cities to hide your administration’s failures. Unlike the Trump administration, Boston follows the law. And Boston will not back down from who we are and what we stand for.”

But while Wu and members of the City Council say Boston Police will not assist federal Department of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents in the Trump administration’s deportation efforts, the Boston Police Department (BPD) has for more than 20 years shared information with federal authorities that activists say has aided ICE in targeting and deporting immigrants.

BPD officials lead the Boston Regional Intelligence Center (BRIC) a collaboration of eight local cities and towns funded in part by federal grants that gathers and shares intelligence with federal law enforcement authorities. Although city officials say there is a firewall between BRIC and ICE, federal immigration agents can easily access the intelligence reports local police departments generate through the inter-agency collaboration.

In recent years, Boston police have aided ICE agents occasionally through direct contact with federal immigration agents and indirectly through their participation in the BRIC, says Fatema Ahmad, executive director of the Muslim Justice League.

“As long as the Boston police have this fusion center and participate in federal task forces, there are ways that their information will get to federal agencies, including ICE,” she said.

Is Boston ICE-free?

Boston in 2014 passed the Trust Act, which prohibits police from sharing information with ICE, asking people their immigration status or detaining people for civil immigration infractions if there is no other criminal charge.

Despite the Trust Act, Boston police have a record of working with ICE agents in ways advocates say undermine the Trust Act. In 2019 the ACLU of Massachusetts requested records of communications between BPD and ICE after a Boston police sergeant called the agency on an undocumented construction worker who filed a workers compensation claim against his employer.

A WBUR analysis of the records from the department’s ICE Task Force found multiple instances of the department’s liaison to ICE sharing information including the address of an undocumented defendant’s parents.

More recently, city councilors have focused attention on BRIC. Although it was set up in the post-September 11, 2001 era as a means to combat terrorism, Boston police officers assigned to BRIC have surveilled protest movements including Occupy Wall Street, the anti-police brutality protests that erupted in the wake of the Ferguson, Missouri police killing of Michael Brown and, most recently, demonstrations against Israel’s bombardment and killing of civilians in Gaza. Critics of BRIC note that the agency has surveilled Boston’s Palestinian Film Festival, but failed to provide intelligence or even an alert to local authorities when the Patriot Front, a violent white supremacist group, marched through downtown Boston in 2022.

BRIC’s information gathering and sharing with federal agencies is bringing increased scrutiny to the agency. After requesting information on the Boston Police Department’s agreements with federal government in February, City Councilor Ben Weber, whose district includes Jamaica Plain and West Roxbury, on Aug. 6 filed a 17F request for memoranda of understanding between the department and federal agencies regarding any information sharing agreements and any rules governing such agreements.

“We’re still waiting for that,” Weber said Tuesday. “What we’ve been told is that there is a firewall in place and we’re not sharing information. I’m encouraged by that, but I’d like to see the memoranda. Let’s take a look and make sure we’re making good on that promise not to share information.”

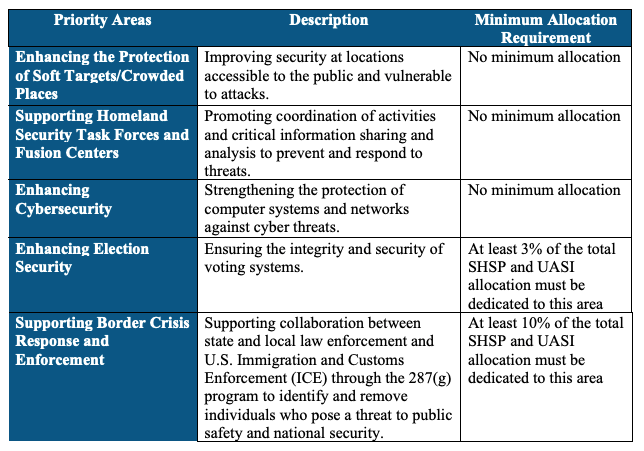

Adding to activists’ concerns about ICE, Wu last week said BRIC will apply for a $12 million Urban Areas Security Initiative grant that requires that 10% of the funding be used for “supporting collaboration between state and local law enforcement and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).”

The grant stipulates the city would have to comply by entering into a 287(g) program “to identify and remove individuals who pose a threat to public safety and national security.”

Mayor Michelle Wu said Tuesday that the city could satisfy the 10% requirement without such an agreement.

“…We already meet new req of 10% to border security through our usual harbor security, not ICE,” Wu wrote in a message on the Bluesky social media app. “If our grant app is rejected, will go to court as we have on other funds.”

Expanding surveillance tech

Beyond the information the BRIC shares with federal agencies, activists are concerned about the agency’s use of new surveillance tools on local activists, including license plate readers and social media monitoring tools.

“We need to pay attention to how our community is being surveilled,” said Mimi Ramos, executive director of New England Community Project. “We need to better understand BRIC, ICE and how the Boston police are working with them.”

Despite a 2022 ordinance that requires the BPD to seek approval before acquiring and deploying new surveillance technology, the department used two new social media monitoring software products in 2023 and 2024, citing what department officials said were “exigent circumstances” in advance of elections held in those years. Department officials continued using one software product, Chorus Intelligence Suite beginning in February of this year, but did not inform the Council until July.

The department’s expanding use of surveillance technology comes as the Trump administration is ramping up surveillance of U.S. citizens and non-citizens alike. In March, Trump signed an executive order requiring the federal government to share data across agencies, raising fears that people’s personal information including sensitive data shared with Medicaid or the Internal Revenue Service would be made more widely available to government officials, including ICE.

Since then, his administration has inked hundreds of millions of dollars of contracts with Palantir, a data analysis and technology firm that specializes in surveillance technology.

Kade Crockford, director of the Technology for Liberty program of the ACLU of Massachusetts, says such information sharing between agencies is a clear violation of the federal Privacy Act of 1974, which places limits on how the federal government can collect and disseminate people’s personal information.

“It’s not clear that the Trump administration regards the law as an obstacle,” Crockford said.

Against the backdrop of expanding federal surveillance, the information gathering at BRIC has sparked concern among activists. In addition to social media monitoring BRIC is using license plate readers that are linked into national networks accessible by police officers in any state. An officer in West Texas assisting ICE agents could, therefore, tap into Flock or Motorola license plate readers in Massachusetts and share that information with agents working here.

On June 15 ICE agents apprehended Paul Dama, manager of a Roxbury restaurant who had applied for asylum in the United States after he was targeted by a Boko Haram militia in Nigeria. Dama, who was on his way to church when apprehended, was working with a valid work authorization.

Did license plate readers give away his location? Did a social media post alert ICE officials to the location of his church? While local officials denounced Dama’s arrest, there’s little information on how or why he was targeted for deportation. Did Boston police provide the license plate readers that gave up his location?

“I think there’s a general consensus in Massachusetts that public safety resources ought to be focused on public safety, and not on aiding ICE,” Crockford said. “But there’s a lot we don’t know about how information may be leaking to ICE. We just don’t have enough facts to know in detail what is happening.”