Voters rejected a high-stakes test as a graduation requirement. Education activists fear the state may be planning a new one

Last year, Massachusetts residents voted in a statewide referendum to end the use of high-stakes tests as a graduation requirement. This year, education activists are worried state officials may be trying to re-institute high-stakes testing.

Last year, Massachusetts residents voted in a statewide referendum to end the use of high-stakes tests as a graduation requirement. This year, education activists are worried state officials may be trying to re-institute high-stakes testing.

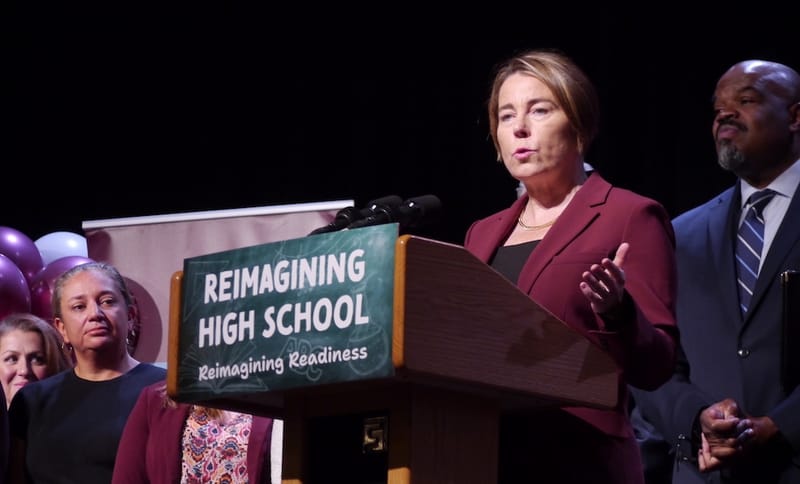

Preliminary recommendations on statewide graduation requirements from Gov. Maura Healey’s Graduation Council include a section that has sparked concern among some.

“Students take end-of-course assessments that are connected to specific courses that are designed, administered, and scored by the state, promoting a uniform standard across Massachusetts,” the recommendation reads.

Monday, education activists and teachers union officials gathered at the State House for a press conference and called on the state to reject any attempts at using such tests as a graduation requirement.

“We want higher standards that reflect authentic work, that challenge teachers and schools,” said Jal Mehta, an associate professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. “Such a system includes a range of assessments, not a single pencil-on-paper test.”

The Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System test, known as MCAS, was instituted after the passage of the 1993 Education Reform Act, through which state officials sought to expand educational opportunities by providing more equitable funding for school districts. In exchange, state leaders demanded schools and school districts be held accountable for student performance.

While the MCAS, as the name implies, was meant to be a “comprehensive assessment system,” student performance was assessed chiefly on students’ scores on a single test. Passage of the 10th grade MCAS exam became a statewide graduation requirement. The ballot referendum voters passed by a 60-40 margin ended the use of the test as a graduation requirement, but the test is still mandatory.

Suleika Soto, a parent of two students in the Boston Public Schools, said one of her daughters doesn’t test well.

“Both of my daughters are successful,” she said. “Both are smart, they’re both determined and compassionate. They just show their learning in very different ways. And that’s exactly why one-size-fits-all tests can never measure a student’s full potential.”

Activists at the State House press conference said the use of high-stakes testing as a graduation requirement leads schools to narrow their curriculum in a practice known as “teaching to the test,” which makes education less engaging.

“When we attach high stakes to an accountability system, like passing the MCAS to receive a diploma, systems will adjust to the nature of the high stakes,” said Massachusetts Teachers Association Vice President Deb McCarthy. “It will become the assessment, and not the learner or the learning, that becomes prioritized. Attaching high stakes to an assessment creates a system that teaches to the test.”

While the MCAS exam is no longer a graduation requirement, the state can hold schools and school districts accountable for student performance on the test. In recent years, the state has done that by putting individual schools and districts in receivership, a form of state control where officials at the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) can appoint receivers to run districts and schools. While last year’s ballot initiative barring use of the MCAS as a graduation requirement does not prevent DESE from using student test scores to put schools or districts in receivership, the state’s appetite for such interventions has waned over the years as years-long interventions in Lawrence, Holyoke, and Southbridge failed to significantly boost students’ performance on the MCAS exam.

Similarly, state intervention into Boston schools labeled “underperforming” by DESE have failed to produce results. The city last year closed the Dever school, which cycled through multiple principals and at one point was run by a startup education management company while under 10 years of state intervention. Attendance at the school plummeted and student test scores did not increase.

Education advocates have long maintained that standardized test scores better measure parental incomes than student learning. Schools and districts such as Lawrence and Holyoke that have come under state intervention are predominantly low-income.

McCarthy, however, says discussions in the governor’s Statewide Graduation Council have largely focused on accountability.

“The word ‘accountability’ was front and center,” she said. “Often I hear those who are opposed to Question 2 opine that without a standardized, end-of-the-year assessment, we abandon the ability to hold educators and school districts accountable for maintaining high standards.”

McCarthy said that rather than focusing on individual districts or schools, the state should look more broadly at accountability.

“Accountability systems need to hold the entire educational community system responsible for all of our learners. Accountability needs to address the opportunity gap and our assessment system needs to finally do the right thing around educational justice.”

Mehta is a proponent of deeper learning, a movement in education aimed at getting students to move beyond rote memorization of facts into understanding the complex elements of a subject and how that subject is connected to other subjects. He advocates for the state to implement assessments that move beyond memorization of facts.

“They might include a student submitting a long essay or an historical paper that they wrote, or an original scientific investigation that reflects their understanding of the scientific method,” he said of possible assessments. “You can’t teach to the test for these kinds of assessments. They grow out of meaningful work students are undertaking. If we want deeper learning, we need deeper means of assessment.”

The Mass Teachers Association is calling on the state to launch a statewide process to re-think education in the schools. Union President Max Page calls standardized tests a “lazy and inaccurate” way to measure student learning and notes that other education systems such as New York City and the states of Kentucky, Indiana and Washington have dropped the use of standardized tests as a graduation requirement.

“We are Massachusetts,” he said. “We should be leading the path, not trying to recreate a system that failed our students.”